One of the things that I've been catching up on is the publication of Bart Ehrman's latest book,

Misquoting Jesus, and the reviews thereof. I'm going to write what I think of the book without actually having read the book, which I know is irresponsible, but a lot of what follows is as much about me and my relationship with what I study as it is about the book, so I don't really care.

Ehrman is chair of the religious studies department at UNC Chapel Hill and the author of the standard text for intro to New Testament classes both at the UW and UVA. My first exposure to NT criticism, besides amateur attempts to decipher the apparatus in Nestle-Aland, the standard Greek NT text, was through taking, and then a year later teaching sections of, the NT-in-translation course at the UW. It is disconcerting for an evangelical with a pretty high view of biblical inerrancy (I don't think I ever subscribed to the idea that God dictated Paul's letters verbatim or anything, but I was definitely more of a literalist than I am now) to confront standard twentieth-century scholarship on the text of the New Testament. So none of the Gospels were written by the people to whom they are attributed, and Paul only wrote half the letters prefaced by his name. Okay. I had not met people who could believe that and still be faithful Christians, although I have since then. And oh, it was miserable trying to teach undergrads who believed in biblical inerrancy. I had to trample on their ideas of what divine inspiration really meant. They must have thought I was an utter apostate. And merely raising the question of whether Paul wrote Ephesians (or whether John Mark wrote Mark, or something like that) caused the most interminable, hideous argument I've ever had with my stepmother, who was convinced I'd lose my faith if I went to UVA. (Much likelier that it would've happened at the UW. But whatever.) This is one reason why, although I'd started my masters program with some interest in NT scholarship, I gave that up. What a bloody minefield.

If you do anything remotely early Christian, though, everyone expects you to know something about the New Testament, and that's fine. I know I'll probably have to teach New Testament courses, and teaching New Testament Greek as a language course was one of the most enjoyable things I've ever done that didn't involve carnal pleasure. I just don't want to be a New Testament scholar. Debating relentlessly about a short collection of books that has been worked over by highly diligent German scholars for a century and a half. Not my cup of tea.

I've learned a lot from doing NT stuff, though. It's what initially got me interested in classics. My Greek NT has received a decade of loving wear. My NT studies led to my interest in church history and my questioning of whether the doctrines I had initially accepted prima facie about, say, whether speaking in tongues was

the evidence that signified the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, were really supportable--and ultimately, whether a complete theology of salvation and Christian growth should place such emphasis on a few discrete texts that talk about being "born again" and being "filled with the Holy Spirit," and so on, as if all of Christian life revolved around what happened in two separate moments. I started to realize that biblical inerrancy,

sola scriptura, and all that didn't really get around the fact that there are multiple ways of interpreting the Bible, and every Christian participates in an interpretive tradition, whether we admit it or not. Which was one factor that led me to choose the interpretive tradition of Catholicism, which frankly acknowledges and embraces its interpretive tradition. That's ten years in a very brief nutshell.

(And yes, I was a Pentecostal. Really, that's a whole 'nother story.)

My point is not to discuss why I became Catholic, but why someone with a similar background to mine, Bart Ehrman, should have such a different response to literary-historical criticism of the New Testament, as he describes in his book and is summarized in a

Washington Post article:

He attended Trinity Episcopal on Vermont Street in Lawrence, but he and his family were casual in their faith. Lost in the middle of the pack in school, Ehrman felt an emptiness settle over him, something that lingered at nights after the lights were out, when the house was quiet.

One afternoon he went to a party at the house of a popular kid. It turned out to be a meeting of a Christian outreach youth group from a nearby college. In private talks, the charismatic young leader of the group told the 15-year-old Ehrman that the emptiness he felt inside was nothing less than his soul crying out for God. He quoted Scripture to prove it.

"Given my reverence for, but ignorance of, the Bible, it all sounded completely convincing," Ehrman writes.

One Saturday morning after having breakfast with the man, Ehrman went home, walked into his room and closed the door. He knelt by his bed and asked the Lord to come into his life.

He rose, and felt better, stronger. "It was your bona fide born-again experience."

...His devotion soon engulfed him. "I told my friends, family, everyone about Christ," he remembers now. "The study of the Bible was a religious experience. The more you studied the Bible, the more spiritual you were. I memorized large parts of it. It was a spiritual exercise, like meditation."

He soon became a gung-ho Christian, a fundamentalist who believed the Bible contained no mistakes. He converted his family to his new faith. Schoolmates went off to the University of Kansas, but he enrolled in the Moody Bible Institute...

For the next 12 years, he studied at Moody, at Wheaton College (another Christian institution in Illinois) and finally at Princeton Theological Seminary. He found he had a gift for languages. His specialty was the ancient texts that tried to explain what actually happened to Jesus Christ, and how the world's largest religion grew into being after his execution.

What he found there began to frighten him.

The Bible simply wasn't error-free. The mistakes grew exponentially as he traced translations through the centuries. There are some 5,700 ancient Greek manuscripts that are the basis of the modern versions of the New Testament, and scholars have uncovered more than 200,000 differences in those texts...

For a man who believed the Bible was the inspired Word of God, Ehrman sought the true originals to shore up his faith. The problem: There are no original manuscripts of the Gospels, of any of the New Testament.

He wrote a tortured paper at Princeton that sought to explain how an episode in Mark might be true, despite clear evidence to the contrary. A professor wrote in the margin:

"Maybe Mark just made a mistake."

As simple as it was, it struck him to the core.

"The evidence for the belief is that if you look closely at the Bible, at the resurrection, you'll find the evidence for it," he says. "For me, that was the seed of its own destruction. It wasn't there. It isn't there."

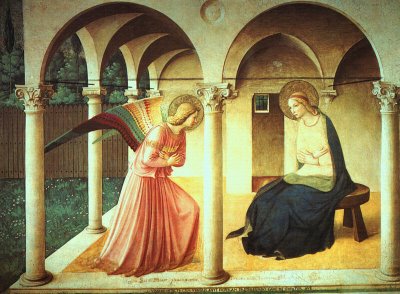

Doubt about the events in the life of Christ are hardly new. There was never clear agreement in the most ancient texts as to the meaning of Christ's death. But for many Christians, the virgin birth, the passion of Christ, the resurrection on the third day -- these simply have to be facts, or there is no basis for the religion...

Ehrman slowly came to a horrifying realization: There was no real historical record. It was, he felt, all incense and myth, told by illiterate men and not set down in writing for decades.

Why didn't I have the same reaction to my NT studies, even though it was Ehrman whose text introduced me to the field, and I came from a similar background?

- I started out as a classicist and therefore wasn't new to the study of ancient texts. Of course there aren't autographs of the New Testament books, just as there aren't autographs of Vergil or Livy, or any number of far more recent authors, for that matter. The authority of the Bible clearly has to be based on something other than the availability of originals we can't possibly possess.

- Where the existing manuscripts disagree, the discrepancies are usually minor. There are enough of them that we can be more certain of what the NT authors actually said than we can about any other classical texts. (Contrary to what some Christians claim, for example in the teaching materials for a church membership class I attended, this doesn't mean the Bible is inspired. It means that we have essentially what came from the pen of Paul or the evangelists, not that they weren't making stuff up. Again, the authority of the Bible can't be based on textual accuracy.) Not to mention that Ehrman makes hay out of some discrepancies which are well known to be at issue, or which other equally reputable scholars believe are less questionable than Ehrman thinks they are. Two examples: 1. Most modern translations either leave out the Trinitarian formula of 1 John 5:8 or have a note explaining it is probably spurious; 2. Bruce Metzger, author of A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament and co-editor of the Nestle-Aland, regards "by the grace of God" (instead of "without God") in Hebrews 2:9 as likely original.

- Why does it have to be all or nothing? If Mark did make a mistake, so what? Does the Bible have to be correct and uncompromised in (literally) every iota, or if we accept that God speaks through human beings, is there room for human personality and fallibility to maculate (a particular choice of words I'll explain in a minute) God's message? As a lot of people like to say, the four gospels are like four different eyewitness accounts of an event, which can differ without affecting the substantial truth of what happened. I don't know if I would mean quite the same thing that they usually mean when they say that, but that indicates what's at issue here. Different eyewitnesses, or different schools of Christian tradition, will not tell the same story, and will inevitably distract us by miscounting asses or angels if our eyes aren't on the real message. A fundamentalist reading of scripture can't really sustain that view, but I don't think I was ever quite a fundamentalist.

A seminary professor who also teaches NT commented, "Sometimes I wonder if we are not all guilty of asking the Bible to do too much," which gets at the heart of the matter. Either we accept the Bible as the word of God, or we don't. If it is, the point of NT study is to learn what God has to say to us, not to see if the Big Grammarian in the Sky ever dangled a participle. If it isn't, all the textual criticism in the world isn't going to make it more convincing. People with both believing and non-believing approaches study the NT as colleagues in research, and I think it's great for biblical scholarship that orthodox seminary professors work alongside agnostic public university professors. But it seems to me that, in motivation if not in content, what they're doing is fundamentally different.

We say "the Bible speaks for itself," which, if you'll pardon me, is bollocks. God speaks for the Bible, because God is God, not the Bible. The Holy Spirit speaks for the Bible, by directing church history so that particular books of the Bible became accepted and continue to be accepted as the written word of God and/or by testifying directly to individual believers that the scriptures are true.

One book that has influenced my own view of scripture is

Revelation Restored by Rabbi David Weiss Halivni. Ezra (who is a figure for later scribes and rabbis) faced the question of how to interpret with reverence a "maculate" (L. "spotted") text that was on the one hand the inviolable word of God, but on the other hand contained errors and inconsistencies as a result of Israel's unfaithfulness to its covenant. Ezra's solution was to preserve such maculations in the text but circumvent them in practice (the rabbis later undertaking the task of explaining discrepancies by the continuous revelation of oral Torah). His prophetic vocation was to preserve the text, as he found it at that moment in Israel's history, as the authoritative, though flawed, version of the Torah. The religious Jew upholds the Torah as holy because it is the word of God, but made imperfect through human frailty. Halivni concludes:

The awareness of maculation in the transmission of the Torah itself, and of consequent difficulties in interpretation, instills a sense of humility, revealing human frailties and weaknesses so great that God's words were tainted by them--and indicates that whatever human beings touch has the potential for corruption. Yet despite the tainting, these words are still the most effective way of becoming closer to God, approaching his presence. We cannot live without these words--there is no spiritual substitute--but while we are living with them, we are keenly aware that we are short of perfect, that along the historical path we have substituted our voice for the divine voice. We are condemned to live this way. (89)

Until we shall know just as we are known.

The Christian Bible isn't exactly analogous to the Torah (as far as dictated revelation, oral Torah vs. Christian exegesis, etc.), but I think Halivni's thesis has some bearing on a Christian understanding of scripture. The believing NT critic, much as I do not envy him, has an important task: to be the steward of an imperfectly preserved sacred text, to seek out as closely as possible a version of the scriptures that is faithful to the revelation God gave us as part of the new covenant--God willing, by the guidance of the Holy Spirit. The written word is how we know God while we await Christ's return. That may ultimately be why I'm not a NT critic: I can't bear that kind of responsibility.